Does the Bible Contain Mistakes?

Is the Bible true? I don’t mean, “Does it contain truth?” I mean, “Does every word in the Bible reveal and teach true facts about reality?”

Did God really part the Red Sea? Did Jonah really spend three days and nights in the belly of a whale? And most importantly, did Jesus actually rise from the dead?

What we’re really driving at is the question of biblical inerrancy. Is the Bible entirely free of error, or does it contain mistakes?

The doctrine of biblical inerrancy

For the first 1700 years of its existence, the church almost universally believed in the inerrancy of the Bible. Some Christians still do today. I’m one of them.

Our reasoning is bound to the nature of the Bible itself as the inspired word of God, where “inspired” carries a double meaning.

First, in that it’s God’s own words (2 Timothy 3:16) and second, that the human authors wrote under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit (2 Peter 1:20-21). Therefore, it’s inspired in both its content and form.

The doctrine of inerrancy, therefore, is an implication of logical necessity. Since every word is God’s, and God can’t lie, then every word must be true. There are no lies or mistakes.

What do we mean by “inerrant?”

Paul Fienberg gives an excellent definition of inerrancy that highlights some important qualifications:

Inerrancy means that when all facts are known, the Scriptures in their original autographs and properly interpreted will be shown to be wholly true in everything they affirm, whether that has to do with doctrine or morality or with the social, physical or life sciences.1

Let’s break down the terms he uses:

- “Original autographs” mean the original copies. What the authors wrote was free from error. This doesn’t exclude the possibility of copying mistakes made thereafter.

- “Properly interpreted” means taking into account things like literary form, methods of composition, cultural and historical context, and intended audience.

- “Wholly true in everything they affirm” means that any statement of fact made by the biblical author, rightly understood, is taken to be true.

Is inerrancy reasonable?

Many see the doctrine of inerrancy as wholly irrational. However, as we mentioned earlier, belief in inerrancy is a logically sound conclusion proceeding from two clearly taught biblical truths:

- the Bible is God’s own word (2 Timothy 3:16); and

- every word that comes from God is true (Psalm 119:142, 160; John 17:17; Romans 3:4)

Admittedly, there’s a degree of circularity here. If God’s Word is our ultimate standard for truth, then our ultimate appeal in defense of its truthfulness must be itself. What alternative is there after all? As J. I. Packer puts it, “Scripture itself is alone competent to judge our doctrine of Scripture.”2

But circularity will occur for anyone attempting to establish a base of ultimate authority. To quote John Frame,

Circular argument of a kind is unavoidable when we argue for an ultimate standard of truth. One who believes that human reason is the ultimate standard can argue that view only by appealing to human reason. One who believes that the Bible is the ultimate standard can argue only by appealing to the Bible. Since all positions partake equally of circularity at this level, it cannot be a point of criticism against any of them.3

Remember, all reasoning begins somewhere

I recall a conversation I had with a university student studying for a master’s in molecular biology. He said he was open to the idea of God, but simply couldn’t believe something that he couldn’t prove scientifically. I assured him that he already did.

I pointed out to him that like all reasoning, modern science depends on a number of prior beliefs, such as,

- The existence of an objectively real world.

- The orderly nature of the world.

- That this objectively real world is knowable.

- That our mind and senses can reliably gather true information about the world.

- That the laws of nature are uniform.

I said, “In order to think scientifically, you first have to assume that all of these things are true, right?” He nodded. “But none are proven by science. Rather, science needs them in order to get started, correct?” He nodded again. I replied, “Then why do you believe they’re true?” He paused for a moment and answered, “I don’t know.” I appreciated his honesty.

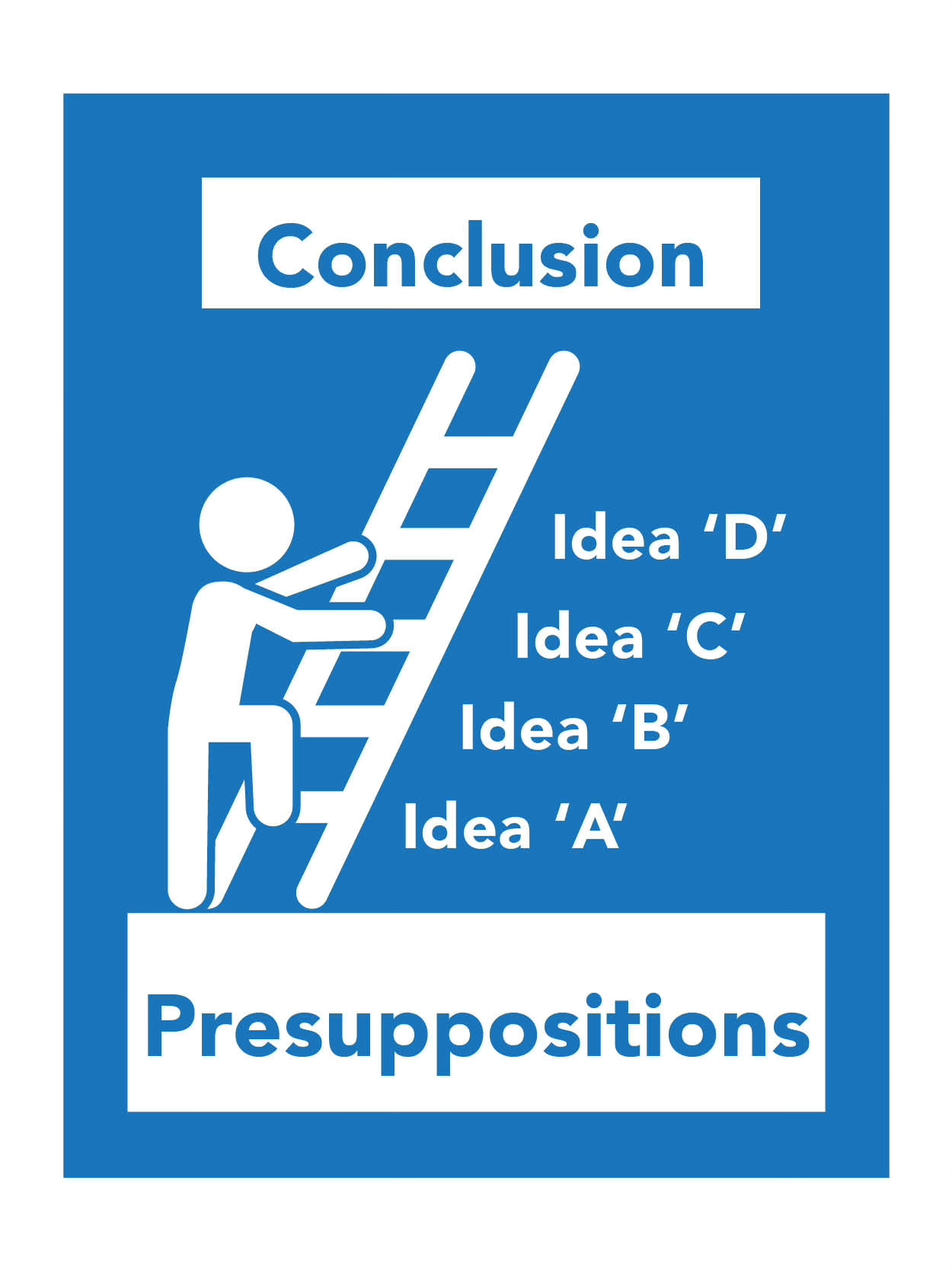

We must remember that when reasoning, we all start from a pre-existing set of assumptions. I liken it to climbing a ladder. Using logic, we move from one step to the next until we reach a conclusion.

All reasoning rests on a set of assumptions from which we draw conclusions.

But reason, like a ladder, requires firm ground on which to stand. This “ground” is our pre-existing set of beliefs or assumptions, sometimes called presuppositions.

Where do we stand to determine the Bible’s truthfulness?

Most people today accept as a foregone conclusion that the Bible is full of errors. They haven’t necessarily determined this for themselves. They just assume that the scholars who say so have proven it.

What they fail to see however, and maybe we do too, is that “proofs” put forward to discredit the Bible also proceed from presuppositions that skeptical scholars just take for granted. As George Ladd observed,

“They interpret the Bible from within the presuppositions of the contemporary scientific world view. Such a world view assumes that all historical events are capable of being explained by other known historical events.”4

In case you missed his point, Ladd is saying that critical scholars assess the Bible using the already held belief that it’s just another historical text. Their presupposition, therefore, is that anything true in the Bible can only be true if it can be explained according to other known historical events.

So, did God really part the Red Sea? Since there are no other sea-partings in history, the answer must be “no.” Did Jesus really rise from the dead? No one else ever has, so it can’t be true. In short, they submit the supernatural works of God to the explanatory assumptions of the natural world, thereby ensuring that supernatural explanations are excluded from the outset.

The illusion of neutrality

The blind spot for those who approach the Bible this way is their belief that they can approach it from a place of rational neutrality. But they can’t. Everyone’s “ladder” is standing on something.

Far from being a neutral investigator, the skeptic brings the supernatural down to his own natural level, “and thus denies in advance, its reality.”

The Bible skeptic’s “ladder” stands on the belief that all books are merely human in origin. He proceeds from this pre-commitment, thereby restricting what explanations he can or can’t entertain before even coming to the evidence. As J. Barton Payne puts it, far from being a neutral investigator, the skeptic brings the supernatural down to his own natural level, “and thus denies in advance, its reality.” 5

Conclusion: So, how can we know that the Bible really is true?

So, does this mean just accepting that the Bible is true, free of any mistakes, without question? “God said it. I believe it. That settles it.” Is that the idea?

Without minimizing the sincerity of faith behind such notions, this doesn’t seem to square with a God who

- invites us to reason with him, (Isaiah 1:18)

- promises to give us enlightenment and understanding, (Colossians 1:9)

- calls us to discernment, (Romans 12:2)

- commands us to add knowledge to our faith, (2 Peter 1:5) and

- saves us to a knowledge of the truth (1 Timothy 2:4).

Proving that God’s Word is true and contains no mistakes is exactly what God wants us to do. He doesn’t just want us to believe it’s true. He wants us to know it! But how? How can we know that the Bible is true?

Gerhard Maier is correct to suggest that proving the Bible true requires using a scientific method suitable to its nature as God’s revealed word. This he says is not critique, but obedience.6 Not a blind obedience, but an obedience of faith that applies all our intellect. The difference is that we’ve moved our “ladder” to different ground. We reason, no longer from the place of “if God’s Word is true, then I’ll believe it,” but “because God’s Word is true, I will follow it.”

That’s the “renewed” mind Paul speaks of in Romans 12:2. In faith we proceed with confidence that because God’s Word is true, we may fully “test and approve” it, knowing that whatever questions we bring to it, it will not fail to reveal what’s “acceptable and perfect.” In other words, the truth.

Notes

1. Paul Fienberg, “The Meaning of Inerrancy,” in Inerrancy, Norman Geisler, ed. (Grand Rapids, MI, Zondervan, 1980), p. 294.

2. J. I. Packer as quoted by Kevin DeYoung in Taking God at His Word, (Wheaton, Ill, Crossway, 2014), p. 23)

3. John Frame, Presuppositional Apologetics, May 23, 2012, [accessed online at frame-poythress.org].

4. As cited by J. Barton Payne, “Higher Criticism and Biblical Inerrancy,” in Inerrancy, Norman Geisler, ed. (Grand Rapids, MI, Zondervan, 1980), p. 90.

5. Ibid, p. 92.

6. Gerhard Maier, The End of the Historical-critical Method, (St. Louis: Concordia, 1977), p. 35