What is Faith and Why Does It Matter?

What is faith? What definition of faith would you give?

There are many words in English that have been so overused that they have almost lost all meaning. “Love” is one such word that, depending on context, can mean sex, lust, selfish desire, selfless giving, emotional ecstasy, or mushy sentimentality. And sometimes even context doesn’t make it completely clear what we mean.

“Faith” is another word that has become especially confusing for Christians or those trying to understand them. We use it often, know that we need to have it, but feel puzzled and confused if anyone asks us to nail down what we actually mean by it.

So what do we mean? What is faith?

What faith isn’t

Perhaps the best place to begin is to clarify what faith isn’t. A good place to start with, is how our culture views faith, because all too often this is where our own ideas come from.

The Santa view

In 1947, one of the best-known Christmas movies of all times, Miracle on 34th Street, was released, telling the story of a department store Santa who claimed to truly be Santa. Fueling the hopes of a little girl and challenging the beliefs of her mother, the story climaxes with a Supreme Court trial in which Santa (Kris) defends his identity as the real Santa. While the prosecutor’s case is built entirely on the basis of what we know (i.e. that Santa doesn’t really exist and therefore the defendant can’t be the “real” Santa), the defending lawyer and main character, Fred Gailey, builds his defense upon the basis of “faith.” In his memorable and emotional closing argument he says,

“Faith is believing when common sense tells you not to. Don’t you see? It’s not just Kris that’s on trial, it’s everything he stands for. It’s kindness and joy and love and all the other intangibles.”

In this sense, faith is what we believe despite what we know to be true. Or as Mark Twain coined it, “faith is believing what you know ain’t so.”

Unfortunately, many Christians maintain such a view of faith, seeing belief in Christ as a pure act of stubborn determination to affirm Jesus as true regardless of the evidence presented to the contrary. In this sense, faith becomes something that we conjure for ourselves. It’s the power of our own convictions divorced from reason.

The Oprah view

One other sense of faith has become popular in our culture, however. This is faith seen as something powerful in and of itself. Such ideas are popularized by contemporary spiritual icons like Oprah or Deepak Chopra. These ideas flow deeply from a New Age philosophy that views our very capacity for having faith as a latent source of power within us that we only need to tap into.

A quote from Oprah’s website by George Woodberry illustrates this idea well:

“If you can’t have faith in what is held up to you for faith, you must find things to believe in yourself, for a life without faith in something is too narrow a space to live.”

In this sense, our faith is in “faith.” What we believe is only of secondary importance. That we believe is all that really matters.

In summary: Culture's views

So, a quick tour of culture gives us two main ways that faith tends to be understood today:

- Faith is belief in opposition to knowledge, and therefore is exercised irrationality.

- Faith is belief in the power we possess within to change ourselves and the world around us, and therefore is exercised idolatry.

Neither of these understandings of faith will do for the Christian, or for any rationally thinking person, for that matter. We must look elsewhere for a useful definition of faith.

What faith is

One of the best-known Bible passages on faith is found in Hebrews 11. The first verse serves as an opening attestation to faith, saying,

“Now faith is being sure of what we hope for and certain of what we do not see.” (NIV)

Taken in isolation, this verse may sound like the “believing what you know ain’t so” version of faith discussed above, but it’s not. The context won’t allow that.

Just prior in Hebrews 10:38, the writer has quoted Habakkuk 2:3-4, in which the prophet sets before God’s people of faith two options:

- Christians can live by faith and please God, or

- They can “shrink back” and displease him.

A commitment to act

But what does he mean by “live by faith” or “not shrinking back”? The writer expresses this in his own words in Hebrews 10:36:

“You need to persevere so that when you have done the will of God [emphasis mine], you will receive what he has promised.”

Far from being mere mental assent to some set of ideas in the absence of evidence, faith is in fact our commitment to act on what God has promised to be true. The “surety” and “certainty” the author mentions in Hebrews 11:1 are mental states resulting in action. It’s aligning our living activities with what God has revealed to be the case about reality, whether that reality concerns himself, ourselves, or the world we live in.

Put simply, faith is living as if what God says is true. And this certainly accords with what the writer of Hebrews says in the rest of chapter 11. Here he presents a thorough biblical-historical sketch of God’s faithful ones and how they illustrate the truth of Hebrews 11:1. By faith, they accepted what God told them was true, and therefore acted accordingly. And far from being in opposition to reason, their actions were based on reason, because they acted according to the knowledge of the truth that God had given them.

This goes against popular ideas that so often pit faith and knowledge against each other. In reality, faith is grounded in knowledge. As Dallas Willard puts it,

“We can never understand the life of faith seen in Scripture and in serious Christian living unless we drop the idea of faith as a “blind leap” and understand that faith is commitment to action, often beyond our natural abilities, based upon knowledge of God and God’s ways.” (Knowing Christ Today, p. 20.)1

If faith is acting in accordance with what we have come to know as true, then why do we struggle so often to live by faith? That’s an important question that impacts every Christian, and one that we’ve explored in a separate post.

Faith of the everyday

The fact is that we exercise faith almost continually every single day, usually without even knowing it. The reason why we treat faith in God as such an unusual thing has more to do with the “unusual” or perhaps more accurately “unfamiliar” nature of God as the object of our faith, rather than any unfamiliarity to exercising faith that we may feel.

Maybe an illustration will help bring clarity to this distinction.

An illustration: The chair

Consider a simple chair. Many times every day we engage in the simple act of sitting. It’s so common, that we do it without even thinking. And yet if we do stop to think about it, this simple act is itself a many-times-a-day exercise of faith.

Here’s why.

Faith, as we clarified above, is acting according to what I know to be true. In the case of a chair, any time I sit down, I’m effectively performing an act of faith based on my knowledge about chairs. The hope of my faith is that I’ll safely attain to the “state of sitting,” allowing my legs a needed break or bringing my mouth closer to the plate with my supper on it.

The chair: The process

We can break down the whole process according to the terms of faith we defined above:

- The OBJECT of my faith: THE CHAIR

- The HOPE of my faith: ATTAINING TO THE STATE OF SITTING

- The KNOWLEDGE on which I base my faith: may be varied and possessed in greater or lesser degrees

- A BASIC KNOWLEDGE OF PHYSICS (i.e. material strength of wood, structural integrity of design, etc.) We may call this knowledge obtained through empirical means.

- CONFIRMATION FROM OTHER “SITTERS” (i.e. we’ve observed or received confirmation from others who have successfully enjoyed the “state of sitting”). We may call this knowledge obtained on good authority.

- OUR KNOWLEDGE OF THE EXISTENCE OF CHAIRS (i.e. we have first-hand personal knowledge of chairs and their properties). We may call this knowledge by direct acquaintance.

The chair: The three stages

So, we have all of the elements needed for faith, but the question now becomes “what is our faith”? In other words, while we have the object, the hope and the knowledge that define and give substance to our faith, where do we find our faith? The answer is in our living response of action. Without this, there is no faith. That’s why James said, “faith without deeds is dead” (James 2:26).

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. So where is our faith in the chair? Here we need to break this simple daily act down a little further.

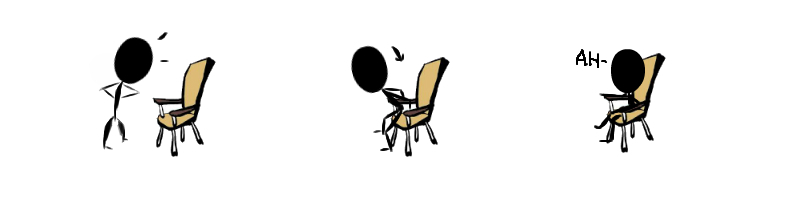

There are essentially three stages to the act of sitting:

- Standing at the chair with the hope of sitting before us.

- The physical motions of placing our body into the chair.

- The final state of sitting itself.

Understanding the chair illustration

Here’s where this picture will help us understand where and what faith is.

If we simply stand before the chair and either mentally or verbally affirm our trust that sitting in it will fulfill our hopes (i.e. the states of sitting), this isn’t faith. It may be an important part of faith that we may call our declaration of faith1, which is of course necessary if we or anyone listening to us is to have any idea of what we’re placing our faith in. But this isn’t faith. At this point, we may only possess some knowledge about the chair (in any of the three forms we listed earlier), but we don’t yet possess faith in the chair, because we haven’t yet begun to act upon our knowledge.

Nor is faith found in the final state of sitting in the chair. Once we’re sitting, we have in fact obtained to the hope of our faith. We’re now in possession, or to use the biblical language, we have received the “inheritance” of our faith, and so we no longer hope for it. As Paul says, “who hopes for what he already has?” (Romans 8:24).

By elimination then, faith must necessarily be found in the second stage, that is, within the physical motions of placing our body into the chair. Faith exists at that point where our action flows out of our knowledge and in living expectation of our hope.

We find our faith only where we are living according to what we’ve already given mental assent to. We “know” the chair will provide the “hope of sitting,” and so now by faith we’ve engaged our lives to enter into that reality. Our faith in the chair lives where we act upon what we have come to know to be true about the chair.

The models of faith and their action

Looking back to our passage in Hebrews, this seems to square well with what the writer affirms about those catalogued as models of faith. They all received revelation from God, which they took as true knowledge. Based on that knowledge and the hope of what was promised, by faith they acted on it. And the writer concludes the chapter stating,

“These were all commended for their faith, yet none of them received what had been promised.” (Hebrews 11:39)

Their faith was found and commended in the living, breathing activities of their everyday lives that conformed to the vision of reality they had been given by God. They were not yet the full recipients of that reality. But their certainty of it (based on their confidence that what God says is true), allowed them to live as if they had already received it. Even when negative circumstances arose that suggested otherwise.

Conclusion: Why a right understanding matters

In exploring the question “What is faith?” , we haven’t been trying to answer “What is Christian faith?”, but the more general question of, ”What kind of thing is faith?” That’s because before we can enter into meaningful conversations about “kinds” of faith (i.e. Christian, Muslim, Humanist, or other), we first need to be clear about what we mean by the word itself.

But even, and perhaps more importantly, to grow as people of faith, Christians need to be clear on what it is that they should be growing. It’s precisely our failure to be clear about that, that leads to so many well-meaning but misguided and sometimes harmful words and activities.

Faith is something most tangible, because it resides in my living, breathing, moment-by-moment response to God’s truth.

Unfortunately, many Christians have allowed culture more than Scripture to inform their concepts of faith, and as a result their attempts to faithfully live out their Christian “faith” result in errors of many kinds. In some cases we adopt the “faith divorced from reason” position, affirming the need to “just believe.” This has the appearance of spiritual wisdom, until someone asks the obvious follow-up question: “How do I ‘just’ do that?” If faith is divorced from reason, it’s hard to offer someone a reasonable answer.

In other cases Christians slip into the mystical “Oprah” version of faith, where knowledge plays little to no role and people are left almost entirely at the mercy of feelings and emotions. In such a view faith is found only by looking deep within your own heart, which is exactly where you don’t want to look except to appreciate the depths from which Jesus has saved you.

Faith properly conceived, however, leaves us in the enviable position of a daily, moment-by-moment capacity to locate, confirm, and even evaluate the health of our faith by asking the most concrete of questions: “What actions have I taken today to demonstrate that I’m living by faith?” This is something we can do regardless of how we’re feeling or what our circumstances are. And it allows us to remove faith from the category that Fred Gailey earlier called the “intangibles” of life. Faith, rather, is something most tangible, because it resides in my living, breathing, moment-by-moment response to God’s truth.

As James remarked about Abraham, that great model of faith,

“You see that [Abraham’s] faith and his actions were working together, and his faith was made complete by what he did.”(James 2:22)

NEXT UP: This article is one of two in the Faith and Reason series. Read the other article in the series.

Originally published March 25, 2013, updated September 15, 2020.

References

- Dallas Willard, Knowing Christ Today, (New York, NY, HarperOne, 2009), 15. Willard makes some great distinctions in his section on knowledge, belief, commitment, and profession that are worth reading.